Improve Gut Health to Improve Brain Function

Key Takeaways

If you read our recent article on gut and glucose, you already know that the gut plays a significant role in maintaining overall health. And you may also remember that some scientists consider the brain to be a part of the gut (from a functional perspective).

It’s because the gut and brain function are intimately connected — the gut influences how the brain functions (from mood to memory to executive function) and vice versa.

In this follow-up on gut health, we’ll explore how the gut and brain influence each other. Plus, you can learn more about improving your gut health to boost your cognitive functions and prevent cognitive decline, mental health issues, and conditions like Alzheimer’s disease.

What Is the Gut?

The gut encompasses more than just your intestines or main digestive organs. It consists of a network of various organs that all work together to carry out various functions.

These organs, in order of first to last, include:

- Mouth

- Esophagus

- Stomach

- Pancreas (an accessory organ to the digestive system)

- Liver (an accessory organ to the digestive system)

- Gallbladder (an accessory organ to the digestive system)

- Small intestine

- Large intestine

These organs communicate bi-directionally (or both ways) to carry out their usual functions. For example, let’s take a quick look at how the liver and gallbladder work together in the digestive system. During digestion, the liver sends bile to the gallbladder. The gallbladder then stores and concentrates it.

When you eat, the gallbladder will release the bile into your small intestine for digestion. The bile will also play a role in regulating the gut microbe community.

Similarly, there’s the brain-gut connection. There’s a part of your body’s central nervous system called the enteric nervous system, or ENS, located in the gut. Some call this the ‘second brain.’

The gut and the brain also communicate with each other for a variety of different functions. Let’s take a deeper look at the relationship between the two.

The Human Brain as Part of the Gut

The brain is considered part of the gut from a functional perspective. What does that mean exactly?

Well, the gut communicates with the brain and guides its many cognitive (and other) functions from memory to attention to overall mood and mental health.

The gut and its microbes produce chemicals and molecules that cross the blood-brain barrier and influence cognitive functioning (more on that below).

Similarly, the brain can affect how the gut functions. These two communicate bidirectionally, like the other organs listed above.

Cognitive Functioning and Cognitive Health

Cognitive functioning of the brain includes a set of processes that occur within the brain and allow us to receive, transmit, transform, store and/or perceive information from the environment.

Cognitive functions include:

- Memory

- Attention

- Perception

Cognitive health is similar to cognitive function, but there’s a key distinction. It’s your ability to carry out your cognitive functions well. That includes being able to concentrate on tasks, think clearly, and remember information, be it about personal events or facts.

In addition to influencing cognitive function and health, the gut also helps with mental health. It can affect dopamine and regulate mood through its communication with the brain.

The Gut Microbe Community

Let’s do a little recap of what the terms “gut microbiome,” “gut microbiota,” and “gut microbe community” mean.

- The microbiome is all of the collective genes in the gut.

- Microbiota refers to the microbes.

- The gut microbe community is the collective of all the different microbes in the gut and how they relate to each other.

The microbe community includes trillions of bacteria, archaea, fungi, viruses, and eukaryotes that have co-evolved with humans for thousands of years.

Each person has 300-1000 unique species. But bacteria are the most abundant and well characterized. After all, there are 38 trillion of them in the gut.

We also have a microbiome in the skin, nose, mouth, and scalp.

The Gut-Brain Connection (The Gut-Brain Axis)

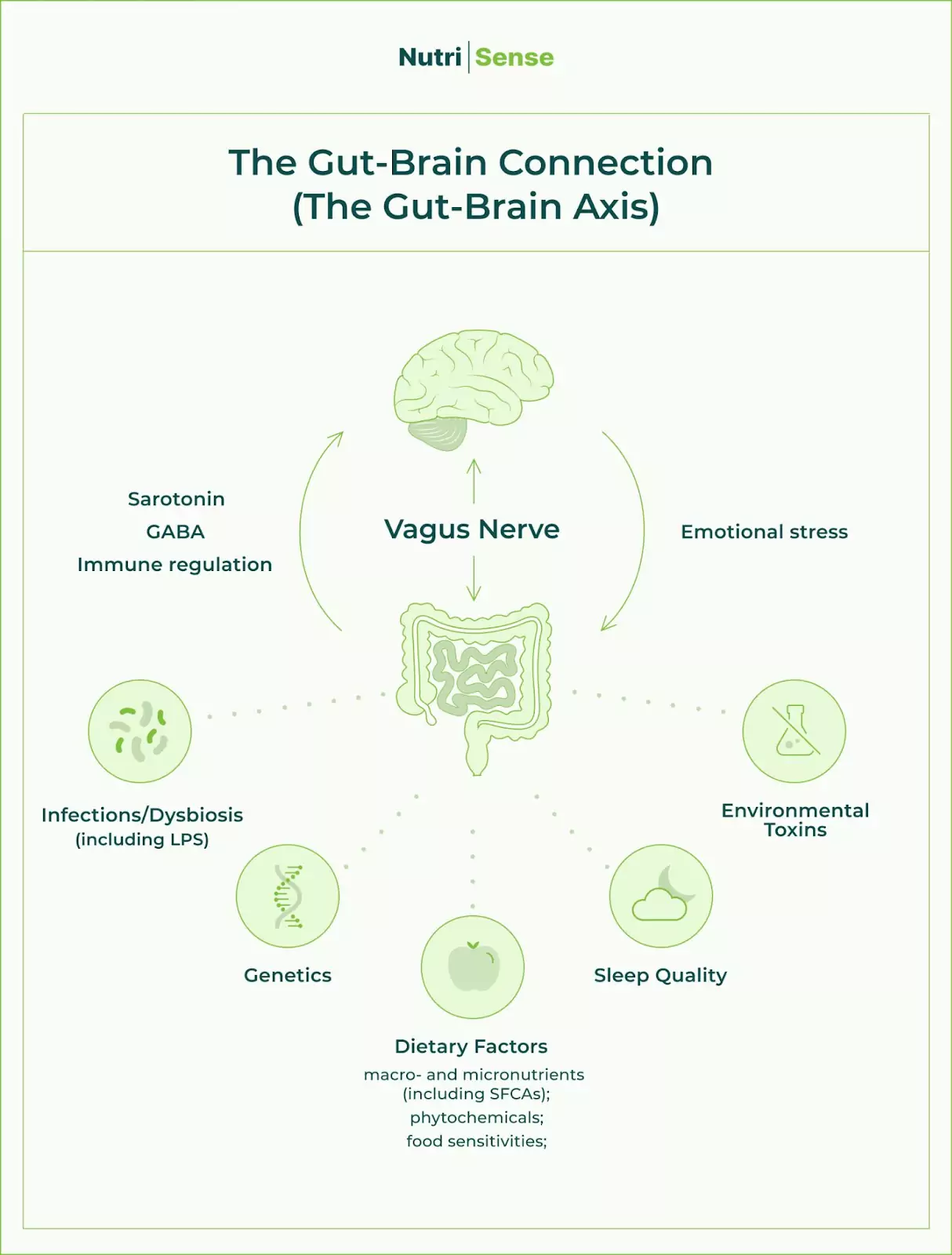

The gut and brain connect and communicate through the gut-brain axis—where the bidirectional communication happens.

In this bidirectional axis, 500 million neurons, or nerve cells, in the gut connect to the brain. Some communicate through the enteric nervous system (a nervous system housed in the intestinal tract).

One specific nerve connecting these two is the vagus nerve. This nerve carries information to and from the brain and organs of the gut.

The gut makes and regulates many neurotransmitters impacting cognition and mood, such as serotonin (stabilizing mood and controlling body clock) and GABA (an inhibitory neurotransmitter that also plays a role in mood).

The gut microbiome may be involved in this process. Here’s how: microbes in the gut produce chemicals that impact how our brain works in many ways. One group of these molecules is called SCFA, or short-chain fatty acids. Examples of SCFAs include butyrate, propionate, and acetate.

These SCFAs can influence the activity of neurons within the brain and, in doing so, can affect mood and cognitive function. They also regulate the blood-brain barrier. The vagus nerve also regulates these neurotransmitters.

Disruption or dysbiosis of the gut-brain axis has been implicated in various anxiety and mood disorders (plus inflammatory conditions such as IBS or inflammatory bowel syndrome).

You may also experience ‘brain fog,’ during which you have difficulty concentrating on the task at hand and/or remembering information. Overall, your mind may feel ‘foggy,’ like it’s hard to ‘see’ what’s going on in your mind (like your cognitive functions).

One way a disruption could occur is when your body registers stress. This axis is part of the stress-response system, where the brain may register and release stressors like cortisol that impact gut function. The gut may experience stressors directly that impact cognitive function.

A specific form of stress is when there is high amounts of inflammation and high LPS, or lipopolysaccharides, present in the body.

LPS is an inflammatory toxin produced by gut microbes that can cause inflammation if it passes from the gut to the bloodstream. It happens when the gut becomes leaky.

And high LPS also plays a role in diseases such as Alzheimer’s and depression, and perhaps even Parkinson’s and schizophrenia.

Improving Gut Health to Improve Cognitive Function

Knowing that the gut-brain axis plays a vital role in your cognitive health and mood is one part of the equation, and the second is learning how to improve your gut health to support your brain health.

First things first, you’ll want to take an individualized approach, and from the general tips and guidance below, figure out which ones work best for you.

We broke down an in-depth guideline from our gut and glucose post (read that post for the details), but here’s a quick summary:

- Focus on a variety of nutrient-dense foods (in whole food form) and ensure you’re getting enough vitamins and minerals for your needs (working with a dietitian or nutritionist can help) to prevent your body from going into stress mode.

- Eat more anti-inflammatory foods to tolerance (like fermented foods, dark chocolate, and sardines) to prevent stress.

- Focus on getting enough good quality sleep, managing emotional stress, and engaging in appropriate exercise.

- The Nutrisense Nutrition Team recommends experimenting with how you time your food intake around exercise to minimize GI symptoms. For some people, that window might be 2 hours before and 45 minutes after workouts, but for some people, that may differ.

- Address additional dietary factors that can lead to physiological stress, such as gastrointestinal disorders like irritable bowel syndrome, conditions like constipation, food sensitivities, or intolerances. In most cases, your dietitian or doctor may recommend avoiding such foods.

- Get plenty of fiber.

- The Nutrisense Nutrition Team also recommends limiting alcohol to three drinks (or even less for some people) since it affects the GI tract motility, absorption, and permeability.

Try These Brain Foods

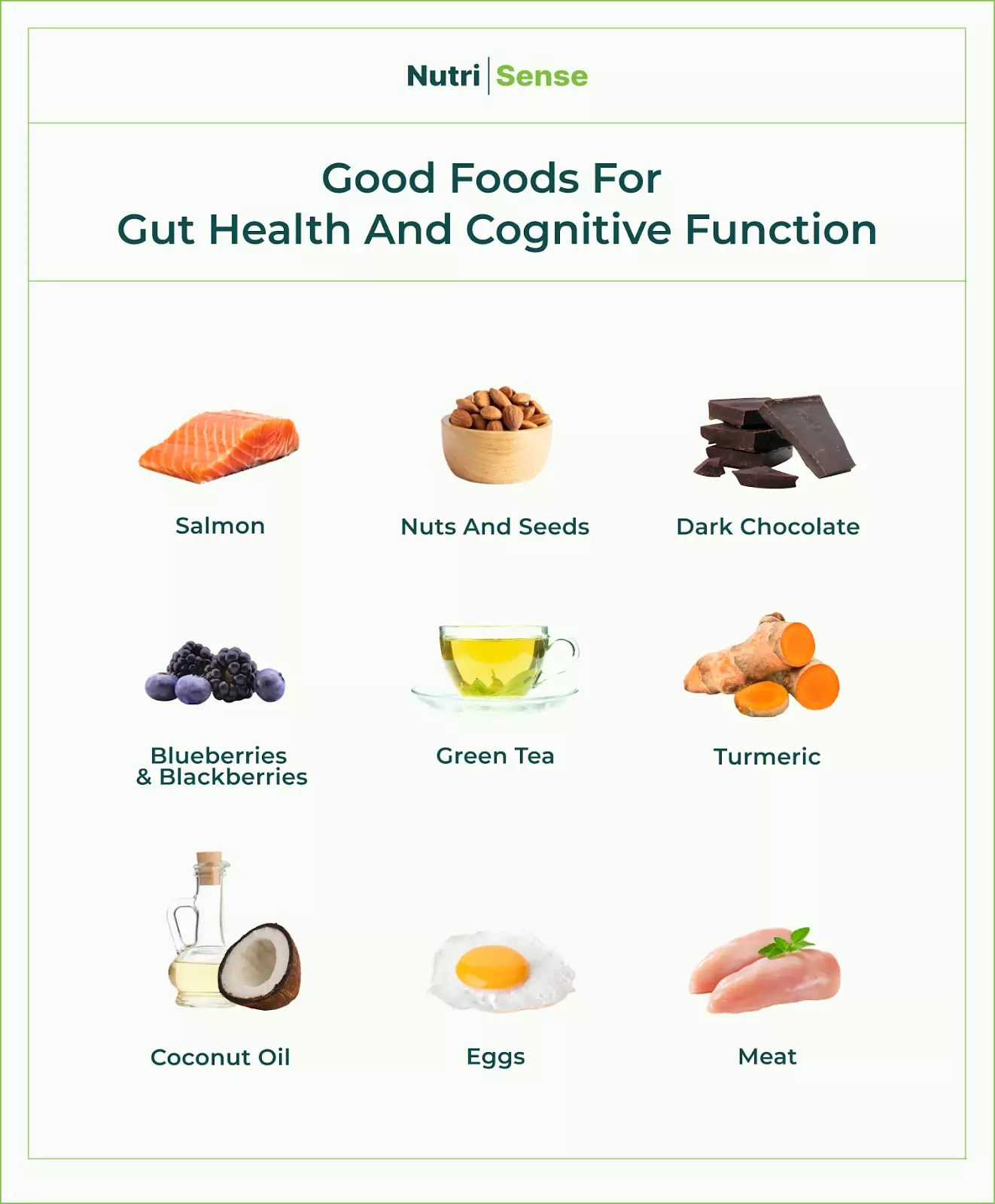

In addition to trying the Nutrisense Nutrition Team's tips for improving gut health, also try these foods and nutrients for boosted cognitive function:

- Omega 3-rich foods such as salmon, nuts, and seeds

- Foods rich in antioxidants such as cacao powder, dark chocolate, blueberries, and green tea

- B vitamins from animal sources (animal protein)

- Anti-inflammatory herbs such as turmeric

- Some high-quality saturated fats, such as coconut oil (though research is limited)

Using a continuous glucose monitor (or CGM) alongside working with a registered dietitian or nutritionist will be very useful here.

You’ll be able to determine which foods are the best for your gut and use that to track what foods help your brain function optimally.

There's so much more to learn about the gut and gut microbiome. We’ve covered the gut’s effects on glucose and the brain, but that barely stretches the surface. So stay tuned for more articles in this series to learn more about your gut!

Find the right Nutrisense programto turn insight into progress.

Go Beyond Glucose Data with Nutrisense

Your glucose can significantly impact how your body feels and functions. That’s why stable levels are an important factor in supporting overall wellbeing. But viewing glucose isn't enough. Nutrisense, you’ll be able to learn how to use your body's data to make informed lifestyle choices that support healthy living.

One-to-one coaching

Sign up to access insurance-covered video calls to work with a glucose expert: a personal registered dietitian or certified nutritionist who will help tailor your lifestyle and diet to your goals.

Monitor and measure what matters

With the Nutrisense CGM Program, you can monitor your glucose with health tech like glucose biosensors and continuous glucose monitor (CGM)s, and analyze the trends over time with the Nutrisense App. This will help you make the most informed choices about the foods you consume and their impact on your health.

Find your best fit

Ready to take the first step? Start with our quiz to find the right Nutrisense program to help you take control.

Heather is a Registered and Licensed Dietitian Nutritionist (RDN, LDN), subject matter expert, and technical writer, with a master's degree in nutrition science from Bastyr University. She has a specialty in neuroendocrinology and has been working in the field of nutrition—including nutrition research, education, medical writing, and clinical integrative and functional nutrition—for over 15 years.